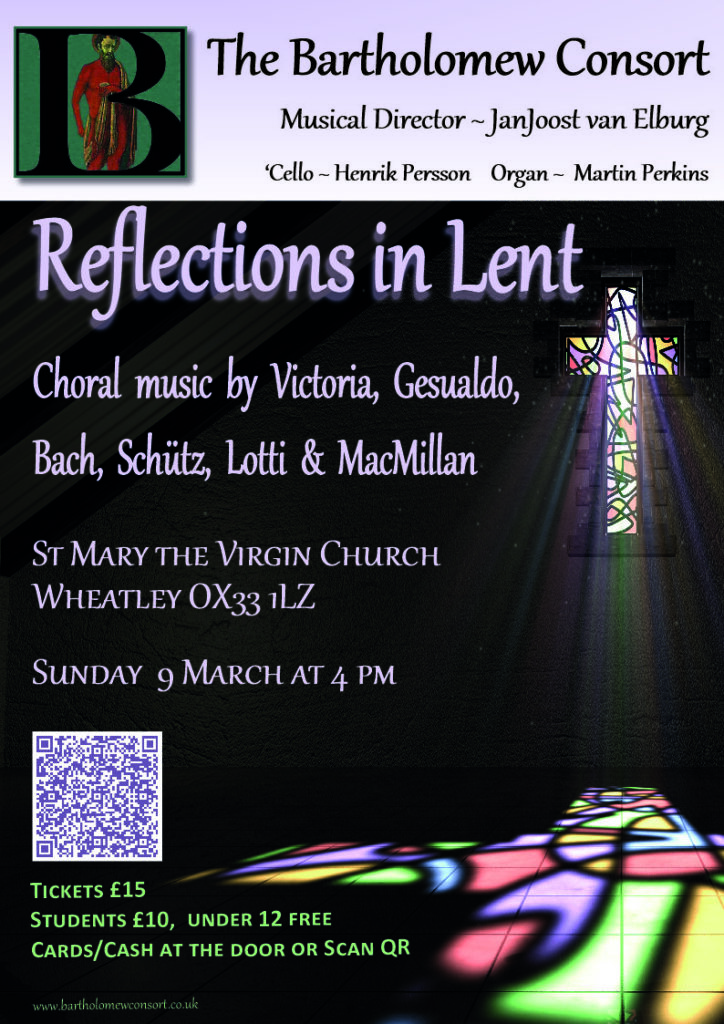

SUNDAY MARCH 16 at 4pm

Choral music by Victoria, Gesualdo, Cozzolani, Bach, Schutz, Lotti & MacMillan

St Mary the Virgin Church , Wheatley OX33 1LZ

Join us for our concert in the St Mary the Virgin Church in

Wheatley for a contemplative and uplifting programme

of music from composers across the centuries.

Gesualdo & Victoria were born in the mid 16th century

and wrote exclusively for the Catholic church; Schütz, born

toward the end of the century, was by contrast

a Lutheran working in Dresden for much of his life.

Cozzolani’s inspiring works were written during her life as a

nun in Santa Radegonda, Milan. Moving on to the late

C17th Lotti spent much of his musical life in Venice,

although with significant associations with music in Dresden.

JS Bach needs no introduction as a devout early C18th

Lutheran, whereas James MacMillan’s contemporary writing

is deeply influenced by his Catholicism.

Whatever the source of inspiration, this will be a musical

experience to enjoy.

Full Programme Notes

Our programme this afternoon features music written by strongly religious composers: Victoria, Gesualdo, Lotti and Cozzolani wrote for the Catholic church, as does MacMillan; Schütz and Bach wrote for the Lutheran church. The season of Lent is a penitential but most inspiring time, and their music certainly reflects this. All of it, except MacMillan’s, was written between the end of the 16th century and the beginning of the 18th – some unaccompanied and some with continuo.

Tomás Luis de Victoria (1548 – 1611) is the most significant composer of the Counter Reformation in Spain, and ranks alongside Palestrina and Lassus as one of the greatest composers of the 16th century. He was a singer, organist, scholar, teacher, and a priest – but it was in composition that he made his most significant impact, writing exclusively for the Catholic church. His music has a depth of purpose that some have compared to the mystical fervour of St. Teresa of Avila, who probably knew him as a youth. With the contrapuntal technique of Palestrina, Victoria fused an intense dramatic feeling that is uniquely personal and deeply Spanish. In the setting of the texts from the Lamentations of Jeremiah, there is an exquisite clarity about his music, beautifully demonstrated in these motets for Holy Saturday, which come from a much larger work for the Officium for Holy Week. In it, he presents polyphonic music to adorn some of the most important services from Palm Sunday to Holy Saturday. Victoria’s balance of formality and intense expression of anguish serve to excite our imagination and admiration.

Heth Misericordia

O Lord, we are not consumed, for his compassions have not failed.

Incipit Oratio Jeremiae

Remember, O Lord, what has happened to us; look and see our reproach.

Our inheritance is turned to strangers, our houses to strangers.

We have become fatherless orphans; our mothers are like widows.

We drink our water for money, we buy our wood for a price.

We are threatened with our necks; we are weary, there is no rest.

Carlo Gesualdo (1566-1613) has a notorious reputation. He came from a privileged family, and early in life showed a lone interest in music. In his twenties he married his first cousin, but his reclusive personality emerged and this led to a decline in the marriage: his wife took on a lover. Gesualdo walked in on them one evening during an intimate moment, and promptly murdered them both in a gruesome way. He even went back after doing the deed, just to make sure they were really dead, and mutilated their corpses. His privilege led to him being cleared of all charges, and after a brief period of musical success, he retreated to his family’s castle in the town of Gesualdo. This murder made him widely renowned both in his own time and ever since. It also, as it were, sets the scene for his music which, in its passionate style, seems to confirm the sensibilities of such behaviour. He wrote the most beautiful music, with extraordinary chromaticism.

The sacred works retain characteristics of his madrigalian compositions but in a diluted form. The two numbers (V and VI) from the Tenebrae Responsories show the music’s contemplative emotional power. Ecce Quomodo is the 24th responsory for Holy Week

Behold how the just man dies, and nobody takes it to heart; and just men are taken away, and nobody considers it.

The just man is taken away from the face of iniquity, and his memory shall be in peace.

Verse: He was dumb as a lamb before his shearer, and opened not his mouth; he was taken away from distress, and from judgment.

The text of O vos omnes is adapted from Lamentations 1:12. It was often set, especially in the sixteenth century, as part of the Tenebrae Responsories for Holy Saturday, as exemplified by Gesualdo’s version here. His approach is one that maintains a free style and outlines his understanding and application of chromatic harmony. This piece contains rapid stylistic shifts and moments that mirror the contemplation of this sorrowful text.

O all you who walk by on the road, pay attention and see: if there be any sorrow like my sorrow.

Verse: Pay attention, all people, and look at my sorrow: if there be any sorrow like my sorrow.

Antonio Lotti (1667 – 1740) was born in Venice and started singing at St Mark’s in 1687. He later became the organist at St Mark’s and composed operas, masses and madrigals. He spent the two years between 1717 and 1719 on leave in Dresden, where he wrote a further three operas. He returned to his work at St Mark’s, eventually becoming maestro di cappella in 1736. His music was influential amongst his contemporaries, and there are surviving manuscripts which were written out by Handel; Lotti’s music is also believed to have been included in Bach’s library.

The Crucifixus section of the Nicene Creed, which describes Christ’s passion and resurrection, could arguably be considered one of the most important texts in the sacred canon. Lotti clearly thought so, as he set the text at least three times: once for six voices, once for eight and once for ten (there is also thought to be a 5-part setting) The Crucifixus in 8 parts is perhaps his best known work, and comes from the Credo in F for choir and orchestra, thought to have been written in Venice before Lotti lived in Dresden. The work begins in a dramatic, possibly operatic manner, with suspensions piled upon suspensions. They render it hugely affecting and intense, building up a richly imitative opening section. The remainder of the piece continues with imitative textures, with suspensions a strong feature of Lotti’s colourful and evolving harmonic language.

The setting for 10 voices, from his Credo in D minor, begins in similar vein with piled suspensions, but remains imitative and is much more strident and energetic than the gentler eight-part version.

One of early modern Europe’s most successful composers, Heinrich Schütz (1585 – 1672) remains one of the most revered in the history of sacred music. Though a majority of his compositions are lost to history, Schütz’s surviving works are of such a calibre that his place in music history is secured. Through patronage as a boy singer at the court of Moritz of Hessen-Kassel, Schütz eventually took up in-depth musical study, travelling extensively across Europe throughout his life, absorbing influences from all manner of sources, including his great contemporary Claudio Monteverdi. Considered to be the first known requiem composed in the German language, the Musikalische Exequien stand as Schütz’s most extensive epitaphic compositions, commissioned for the funeral of Prince Heinrich of Reuss in 1636, who had left a fastidious will containing detailed instructions for every element of his funeral. He stated February 4, the traditional burial date of Simeon, as the specific date for his internment. His family requested that the composer set biblical texts represented on his coffin to music for the funeral service in a sequence mirroring their arrangement there. Consisting of three parts played throughout an elaborate service, Schütz’s work anticipates the great oratorios of Bach while synthesizing the major traditions of sacred orchestral and choral music from past composers and his own era. Unlike the familiar fire and brimstone of the Latin Mass for the Dead, the texts selected by Prince Heinrich offer more contemplative reflections on life’s cyclical sorrows and the promise of eternal salvation. The second part of the work, the Motet, Herr, wenn ich nur dich habe is a tour de force for double chorus. Here, Schütz exploits the antiphonal techniques of Gabrieli in the interplay between the two groups. This technique is heightened in the concluding Canticum, Herr, nun lassest Du Deinen Diener fahren, which features a theatrical arrangement of the main chorus singing the text of the Canticle of Simeon juxtaposed against three unaccompanied singers who signify heavenly voices in the distance. This arrangement brings the whole piece to a blissful close in contemplation of salvation.

II. Motet

Lord, if I only have you, I care nothing about heaven and earth. Even if my body and soul are wasting away, you, God, are always the comfort of my heart and my portion.

III. Canticum

Intonation: Lord, now you let your servant depart in peace, as you have said.

Chorus I: For my eyes have seen your salvation, whom you have prepared for all peoples, a light for revelation to the Gentiles and for glory to your people Israel.

Chorus II: Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord; they rest from their work, and their works follow them. They are in the hand of the Lord, and no torment touches them. Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord.

Like her sister, aunt, and nieces, the Benedictine nun Chiara Margarita Cozzolani (1602 – 1677) took her vows in her late teens. She had been born into a well-off family in Milan, and might have received her early musical training from members of the well-known Rognoni family, instrumental and vocal teachers in the city. Her four musical publications appeared between 1640 and 1650. Later, she served as prioress and abbess at Santa Radegonda, helping to guide the house through troubled times in the 1660s, as it came under attack by the strict Archbishop Alfonso Litta, concerned to limit nuns’ practice of music, along with other ‘irregular’ contact with the outside world. The convent was famous for its sisters’ music-making on feast-days; the fame of Cozzolani and her house during her lifetime is evident in writings from her contemporary Filippo Picinelli: “The nuns of Santa Radegonda of Milan are gifted with such rare and exquisite talents in music that they are acknowledged to be the best singers of Italy…. Among these sisters, Donna Chiara Margarita Cozzolani merits the highest praise, Chiara [literally, ‘clear’, Cozzolani’s religious name] in name but even more so in merit, and Margarita [literally, ‘a pearl’] for her unusual and excellent nobility of [musical] invention…”. She was of course only one of over a dozen nuns in seventeenth-century Italy who published their music – such as Lucrezia Vizzana and Isabella Leonarda – but the ongoing tributes to her and to the musical culture of her house are remarkable on any count.

The Magnificat is scored for eight voices with basso continuo. The vocal resources of S. Radegonda allowed Cozzolani to apportion a wide variety of textures to the verses of eight-part writing. The Magnificat uses recurring motifs. The material of the first verse is worked into various places of the canticle, but it also repeats parts of adjacent verses in the interest of contrast, textual and musical, as in the case of the forceful ‘dispersit superbos’ followed immediately by the humble ‘respexit humilitatatem ancillae suae’ from an earlier verse. The setting also uses direct antiphony between the two groups of four voices (‘a progenie in progenies’), similar to the music of Cozzolani’s elder contemporary, Monteverdi.

J.S Bach (1685 – 1750)wrote Christ lag in Todesbanden – one of his earliest church cantatas – in 1707, when he was 22. It is a chorale cantata, in which both text and music are based on a hymn. Its source was Martin Luther’s fiery and dramatic hymn of the same name, the main piece for Easter in the Lutheran church. The composition is based on the seven stanzas of the hymn and its tune, which was derived from Medieval models. It is a bold, innovative piece of musical drama, quite jazzy in places, with the focus on the central fourth stanza, Es war ein wunderlicher Krieg, a busy contrapuntal movement about the battle between Life and Death.

How fierce and dreadful was the strife when Life with Death contended;

For Death was swallowed up by Life and all his power was ended

God of old, the Scriptures show, did promise that it should be so.

O Death, where’s now thy victory? Hallelujah!

The final chorale:

We eat and live well on the right Easter cakes, the old sour-dough should not be with the word grace,

Christ will be our food and alone feed the soul, faith will live in no other way. Alleluia

The Scottish composer Sir James MacMillan (b. 1959) is a vocal proponent of contemporary sacred music, and his work, strongly influenced by theological themes and language, is a luminous expression of his strong Catholic faith. The monumental and exquisite setting of Psalm 51: 3-21, Miserere, a penitential text from the Matins service of Tenebrae, which takes place during Holy Week (famously set in the 17th century by Gregorio Allegri), was commissioned in 2009 for a festival in Antwerp where it was performed by The Sixteen. The text, which progresses from guilt and sin to hope and optimism, is scored for a single choir with divisi and soli in each voice-part, with chanted passages in close harmony for male and then female voices. It draws on many characteristics of the composer’s mature choral style, from folk-like melodies to Scotch snap rhythms, from bitonality to canonic textures, and from plainchant to dramatic and explosive expressions of feeling, reinscribing past music and rituals as part of refashioning the contemporary imagining of religion. It is through-composed, but structured in a series of interlocking sections and bound together by a number of recurring motifs. MacMillan admits a nod towards Allegri’s masterful 1638 setting by referencing the psalm chant, but his own version of the chant is harmonised, once in a relatively traditional manner, and then later, ethereally and with floating drones. The opening melody, based upon a minor mode, eventually recurs at the very end in its major, with the sense of resignation and hope.

Have mercy on me, O God: according to the greatness of thy mercy

And according to the multitude of thy tender mercies blot out my iniquity

Wash me thoroughly from mine iniquity: and cleanse me from my sin

For I acknowledge my iniquity: and my sin is ever before me

Against thee only have I sinned, and done evil in thy sight: that thou mayest be justified in thy words, and prevail when thou art judged

For behold, I was shapen in iniquity: and in sins did my mother conceive me

For behold, thou hast loved truth: thou hast shewed me the uncertain and hidden things of thy wisdom

You shall sprinkle me with hyssop and I shall be clean: thou shalt wash me and I shall be whiter than snow

You shall give joy and gladness to my hearing: and the humble bones shall rejoice

Turn away thy face from my sins: and blot out all mine iniquities

Create in me a clean heart, O God: and renew a right spirit within me

Cast me not away from thy face: and take not thy holy spirit from me

Restore unto me the joy of thy salvation: and strengthen me with thy leading spirit

I will teach the wicked the ways Deliver me from bloodshed, O God, the God of my salvation: and my tongue shall sing of thy righteousness. Open my lips, O Lord, and my mouth shall shew forth thy praise. For if thou hadst desired sacrifice, I would have given it: thou hast no pleasure in burnt offerings. The sacrifice unto God is a broken spirit: a broken and contrite heart, O God, thou wilt not despise. Do good, O Lord, in thy good pleasure, to Zion: that the walls of Jerusalem may be built. Then wilt thou accept the sacrifice of righteousness, oblations and burnt offerings: then shall they lay calves upon thine altar.